A glass of Nuits 1947 with bottle and decanter in the background. A regular night in chez moi.

So, a few years ago I discovered that you can buy booze on eBay. Not normal eBay, of course, but foreign eBay – eBay.de to be precise. After searching around online for a while and dodging the exorbitantly priced bottles of dross, I stumbled upon something that looked rather good – a bottle simply labelled “1947 NUITS”.

“Nuits” is a somewhat archaic name for the town commonly known as Nuits-Saint-Georges, after its most famous Premier Cru vineyard “Les Saint George”. I had a wonderfully underwhelming visit to Nuits on a cold March afternoon about 3 months after this episode, whilst LS was living in Dijon. That, however, will have to be the subject of another post when I tell you about the comparison between the Mercurey vintages of 1928 and 2010 that we made that evening.

A photo from that trip to Nuits-St-Georges. The station had platforms, unlike most of the others on that trip which were just gravel by the side of the tracks.

The bottle had significant ullage, no capsule, and the label was only slightly attached, but this was a bottle of red wine – Burgundy, no less- from only two years after the end of the war. Michael Broadbent describes the ‘47 Burgundy vintage in his magnum opus Vintage Wine (2002) as being “A wonderfully rich vintage following an excellent growing season… more stable than their counterparts in Bordeaux.” He also goes on to quote a somewhat obscure 17th century poet to advise that people with an interest in this vintage “Gather ye rosebuds while ye may”.

In the spirit of carpeing the diem as Broadbent suggested, I placed a bid on the bottle and won it for the princely sum of about sixteen quid, plus P&P.

The bottle had lain in a cellar in the Dutch town of Krommeniedijk, and goodness knows how it had got there, but what I do know is how it got to me. Despite the fact that it was posted in Holland after the Royal Mail’s last Christmas posting date, the good old German courier company they used got it here in time for the big day. Hooray for German efficiency.

Unfortunately, despite the fact that the bottle had arrived at my parents’ house in time, there was no way we could drink it on Christmas day 2012 as I had planned. You see, sitting around for 65 years does some rather interesting things to wine.

How I imagine that old Dutch cellar to look… (Photo credit: Steffen Hausmann, via Wikimedia commons)

There are many complicated chemical processes which occur during the aging of wine, but the one that concerned me most was one called polymerisation. You see, there are molecules in wine called tannins. You’ll recognise tannins from their appearance in over-brewed tea, or young red wine where they make the inside of your mouth feel furry.

Tannins are long chain molecules that primarily come from the skins and stalks of grapes. They give a wine mouthfeel which is often described as “structure” in tasting notes. As a wine ages, these chains of tannins link together and make longer chains. This changes the mouthfeel of the wine and can often lead to high-quality wines going through a “dumb phase” where the perception of tannins is overwhelming all the other flavours.

With time, however, the tannins get so long that they eventually become too big to dissolve in the liquid and fall out as sediment, along with a few other things. This is why old wines are sometimes decanted and the last half-glass or so left behind in the bottle to prevent the sludge getting in the serving. This is why aging wines need to be left still.

Travelling in the back of a DHL truck for several days was not optimum conditions, and upon arrival, I shone a torch into the wine to discover that it was about as clear as a muddy puddle. I gently stood the wine upright in a cold room and left it, untouched for as long as I could. It took until New Year’s Day for the wine to approach limpidity. At least this gave me plenty of opportunity to marinade some beef shin for a boeuf bourguignon to serve with it.

Between receiving and drinking the bottle, I took a trip to St. James to do some Christmas shopping. I stopped in at Berry Bros. & Rudd and chatted with Francis Huicq, the manager of the shop. I explained what I had and showed him a picture of the bottle. He was somewhat surprised and asked me where on earth I had bought the bottle. I explained its provenance and asked him if he knew anything about the maker, a rather mysterious “Société VINICOLE à Beaune”, which showed precisely zero returns on Google.

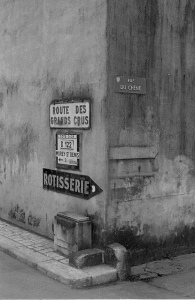

On the road from Dijon to Beaune at Gevrey-Chambertin.

(Taken by Matt, 2013, HP5+ film, HC-110 developer Dilution H. Canon EOS 300V)

Monsieur Huicq explained to me that the Société was the winemakers’ school in Beaune, which he himself had attended. He told me that the wine would have been made by the students under the instruction of master winemakers, and would be of the highest quality. He was also rather surprised that I had managed to obtain a bottle of their wine, given that he had only found one way of getting hold of it: by visiting the Société and buying it there in person.

So, after all this storytelling, you’re probably wondering “what does a bottle of 65 year old Burgundy taste like?” Well here goes… it was unlike any wine I’ve tasted before or since, and prior to this I’d always kind of thought that the words used to describe fine wines were kind of guff, but this stuff actually tasted like the things described here, but kind of all at once. Anyway, here are the notes I made at the time as I shared the bottle with my family, so some of the words are theirs:

Ullage: Significant, ~9cm

Cork: Wet, sodden despite standing upright for nearly 2 weeks. Collapsed in half when drawn and bottom had to be pushed into wine (and subsequently I had to decant it through a cloth to make sure no bits ended up in glasses – originally I had planned to pour straight into the glasses as is customary with Burgundies). Not apparently branded, very black on almost all surfaces with contact with glass. Capsule was missing. Label only just attached. Bottle shows signs of age, dirt, dust. Deep punt with a ‘bobble’ in the middle. Appears to be machine made because it has a seam and the number 97 in the punt.

Colour: Brown, orangy when light shone through. Not very limpid. Faint redness still visible. Dried blood. Colourless at the rim. Not limpid, possibly due to being posted – although it was stood upright and still for nearly two weeks prior to opening.

Nose: Variously; oak, cedar, ‘peppery’, ‘cigar box but cleaner’, ‘wood’, ‘figs when you crunch the seeds’, ‘pencil shavings without the graphite’. Notably no sherry smell and no nuttiness, which is amazing, given the ullage of around 9cm. Autumnal character, with wet leaves/forest floor tones.

From the glass with the most sediment – put to one side with a sheet of paper on top and assessed later: Volatile acidity smelling like the glue that you use on shoes; acetone; ‘almost almondy’

Taste: As nose, but strangely reminiscent of blood from a nosebleed. After 4h in glass, reminiscent of coins, copper, sucking the zip on your coat as a child (this was the last glass I mentioned earlier – the better ones having been drained). Despite saying this, it was not unpleasant.

Finish: Slightly metallic, fairly long, but not remarkably so. EDIT: I can still taste it over an hour since finishing the last drop. It’s much longer than I gave it credit for!

Overall: I wish I had more of this. It is remarkable that it has survived for so long. I’m pretty sure that this bottle wasn’t the best that this wine could have been, what with the ullage and the browning (although not vinegary or sherry-like at all). If I ever saw another bottle of this on sale again, I would definitely buy it to compare – assuming it was in better condition.

Opened with a Boeuf Bourgignon, which was probably too intense a flavour for this delicate, ancient wine, but did go nicely together.

P.S. HLM described this as being nicer than the Ch. Roc Taillade 1999 we had shared a week previously (which was a little over the hill, I guess that suggests that this bottle wasn’t, despite the browning). I think I’d almost certainly agree.

So there we have it, my amateurish attempt to describe the taste of a bottle of wine made years before my grandparents had even set eyes upon each other, yet more youthful than one made two full generations later. I hope you’ve enjoyed reading this. If it hasn’t bored our readership to death, I might publish some more tasting stories in future posts. Give us some feedback, let me know what you think.

Matt